Frankenstein in Baghdad was a fascinating read for me for multiple reasons. One of the biggest factors that stuck out to me was the way in which an adaptation of a classic story was used in a different sense to convey a political meaning.

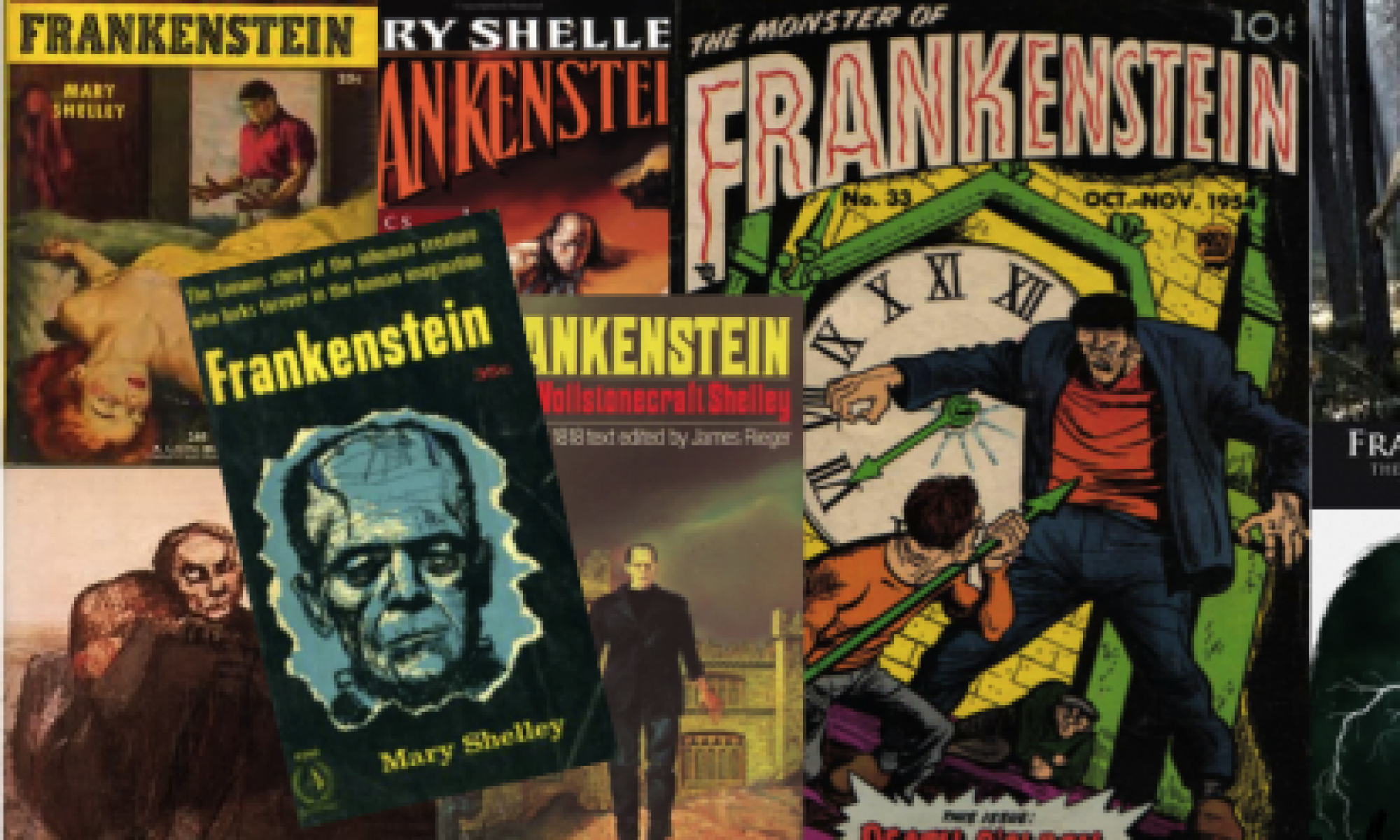

The original Frankenstein, as legend holds, was written by Mary Shelley as part of a competition to write the scariest story on a stormy night indoors. It was originally intended as a horror story intended to frighten and entertain. Ahmed Saadawi flips this original purpose on its head, subtly infusing his adaptation of the Frankenstein story, Frankenstein in Baghdad, with political meaning and implications.

This new version of Frankenstein involves a narrative intended to make a statement on the state of affairs, violence, and corruption in the city of Baghdad, Iraq. As opposed to creating the monster out of scientific curiosities and a desire to have a power over life, Baghdad’s Frankenstein has roots in a desire to create a full body to be buried. It creates a powerful statement on the level of terrorism in the country at the time. It paints in our heads the idea that mass amounts of people were being killed in gruesome ways that a full body for burial was rare at that point in time. In addition, instead of seeking revenge on his master for neglecting him, as in Mary Shelley’s version of Frankenstein, this monster seeks to exact revenge on the ‘criminals’ who killed the victims that were now a part of his body. This implies that government and foreign entities were unable to stop the violence and that their efforts were ineffective. This is further reinforced by the man who allows the Baghdad Frankenstein to kill him in order to ‘give him some new parts’ and in that way contribute to the cause. This creates for us the sense that the people in Iraq were desperate at the time, as they watched countless people murdered in terrorist-related acts, and the futility of the powers-at-large to arrest the violence. There are countless other examples in Frankenstein in Baghdad that contain political or societal undertones.

This experience has really taught me how to read and look at adaptations. This is the first back-to-back textual adaptation we’ve read this semester, and it has really opened my eyes in terms of how to analyze intertextual relationships. It has opened my mind to now seek the answer to the question, “Why would the author choose to rewrite a pre-existing story in a new context?” It has been planted in my head now that when adaptations are created, there is usually a motive or underpinning idea behind the creation of an adaptation. I found it fascinating that Ahmed Saadawi was able to craft an adaptation of Frankenstein in such a way as to create a political statement about his city and country. I enjoyed seeking these pieces of the new author’s view inside a familiar narrative. Perhaps that’s why adaptations are so effective. When a common-knowledge narrative is changed into a new context, the author’s own point of view shines through brightly. It seems to be a fantastic medium to have an intertextual conversation, as well as promote a message.