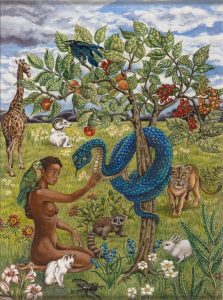

The story of creation and the fall of man are two of the most recognizable stories told. In contrast to the biblical representation of Eve as a sinful woman who leads man into temptation, Rose Piper’s Eve and the Serpent painting portrays Eve as innocent and naive. In the center of the painting, Piper illustrates Eve looking intently at the serpent on the tree her eyes filled with wonderment and fascination. However, the serpent is winking while facing the viewer. It is almost as if it is showing the audience that we know something that Eve does not, emphasizing her naivety. Through Piper’s vision, Eve is not the one to blame for the fall of man she is a victim of the serpent’s master manipulation. Piper changed the story from “The woman you put here with me—she gave me some fruit from the tree” (Genesis 3:12) and “Because you listened to your wife… Cursed is the ground…” (Genesis 3:17) to “The serpent deceived me” (Genesis 3:13). The serpent is painted a vibrant blue color surrounded by a contrast of bright red fruit. Red is often depicted as a sinful color affiliated with anger and passion while blue is often associated with calmness and tranquility. The snake purposefully lured Eve into a false sense of security. The serpent’s wink in the painting elucidated that he is up to something. Us, the viewers who have heard the story before, know that he manipulates Eve into eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of life.

Mary Shelley’s Warning to Society

Frankenstein, in its many forms, is a “ghost story” centralized around the idea of pursuing knowledge and scientific discovery. Frankenstein’s crusade to discover the secret of life drove him to madness and eventually his demise. Shelley’s story begins with Frankenstein adamantly warning his travel companion, “You seek for knowledge and wisdom, as I once did; and I ardently hope that the gratification of your wishes may not be a serpent to sting you, as mine has been” (pg 17). He then goes on to explain the nature of his “great and unparalleled misfortunes” that has “stung” him. From Frankenstein’s recollection, his creation of the creature caused him nothing but torment and devastation. Frankenstein interprets his scientific discovery as a cautionary tale of the dangers of pursuing knowledge. “Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow” (pg 32). According to Frankenstein and his experience with pursuing knowledge, he believes it is better to live a life of ignorance blind to the unknown. However, in volume two, Frankenstein’s creature tells a different story. The creature recounts the negligence of his creator, who left him to fend for himself in a foreign environment. “Cursed creator! Why did you form a monster so hideous that even you turned from me in disgust? God in pity made man beautiful and alluring, after his own image; but my form is a filthy type of your’s, more horrid from its very resemblance.” He also mentions his experience of abuse at the hands of society. The creature reveals that his misfortune and anguish provoked him to seek revenge. “I, the miserable and the abandoned, am an abortion, to be spurned at, and kicked, and trampled on. Even now my blood boils at the recollection of this injustice” (pg 160). The switch in perspective gives us insight into the creature’s thoughts and emotions. Being able to do so gives us a different interpretation of pursuing knowledge and scientific discovery. The discovery of science and knowledge is not perilous but can develop into something dangerous through maltreatment and abuse. So the message changes from knowledge is dangerous to it is only dangerous when it is misused by society. “Am I to be thought the only criminal, when all human kind sinned against me?” (pg 160). Knowledge has great power so in order to avoid the consequences that entail it people need to be accountable for their discoveries.

Even though Mary Shelley wrote this novel two hundred years ago, the message she conveys is still relevant in today’s society. Frankenstein was one of the first novels to introduce the foundation for scrutinizing the integrity and ethics of research and development projects. In today’s society, we have encapsulated the words advancement and progression in our basic definition of science. So much so that many people assume that scientific advancement is synonymous with better and easier lives. For instance, self-driving cars are expeditiously gaining popularity. The idea of driverless cars presents many benefits like increase driving efficiency and reduce traffic accidents. However, there are many unintended consequences that accompany autonomous vehicles. Self-driven cars need to be able to react to every unexpected situation on the road and accidents are bound to happen. What if a child jumps in front of a car and there is not enough time to break? Does the car continue and hurt the child? Steer towards the sidewalk, possibly hurting pedestrians? Does it collide with oncoming traffic and possibly hurt the driver and the passengers? Who determines who the victims are in case of an accident? And who is to responsible?

The Truth in Silence

In the 1986 adaptation of Robinson Crusoe, J. M. Coetzee tells the “real” story of Cruso and Friday through Susan, the “female castaway.” Throughout the novel, Susan becomes immensely infatuated with finding the truth whether it is about Cruso, Friday, or her daughter. Susan finds that there is a need to tell the “real” story of the island castaways so much so that she wanted to have a book published. She approaches Foe claiming to be “seeking a new situation.” Then pitches her story insisting that he has never heard a story likes hers and that she was the “good fortune we are always hoping for” (48). So her story is more than just setting the record straight, it is to gain fortune in order to care for her and Friday.

From the very beginning, she is very determined whoever writes it will write the whole truth. “I will not have any lies told . . . I would rather be the author of my own story than have lies told about me . . . If I cannot come forward, as author, and swear to the truth of my tale, what be the worth of it?” (40). However, her actions regarding Friday seem to contradict that. In Coetzee’s version, Friday’s tongue was cut out and he is not able to speak. Susan habitually speaks for Friday and presumes his thoughts and feelings without fully knowing if they are in fact true. For instance, when Cruso was dying Susan persuaded the ship’s captain to permit Friday to go into Cruso’s cabin because he “would rather sleep on the floor at his master’s feet than on the softest bed in Christendom” (41). While she reiterates many times to Foe to write the whole truth and nothing but, it does not stop Susan from putting words in Friday’s mouth and telling “his” story. She later admits this to Foe when she refuses to tell him about the time she spent in Bahia.“Friday has no command of words… I say he is a cannibal and he becomes a cannibal; I say he is a laundryman and he becomes a laundryman . . . No matter what he is to himself… what he is to the world is what I make of him” (121-122). Susan claims she wants the story to be about the time they spent on the island. The only stories she is willing to tell Foe is how she came to be marooned, Cruso’s shipwreck, Cruso’s early years, and Friday’s story. She discloses the fact that Friday’s story is a “hole in the narrative”. Nevertheless, this does not stop her from trying to filling in the gaps in any way she can. Susan does attempt to find a way to establish some form of communication with Friday through art, dance, and music but Friday stays silent. Does he not understand or is he staying silent for the same reason as Susan? “I choose not to tell it because to no one, not even to you, do I owe proof that I am a substantial being with a substantial history in the world . . . for I am a free woman who asserts her freedom by telling her story according to her own desire” (131). So Susan’s choice of silence is her way of controlling how her story is told. She does not seem to realize that she is controlling Friday’s story. Perhaps she does not see him as a “substantial being” with a “substantial history.”

Coetzee, John M. Foe. Viking, 1987.

The Fate of the Sea

From the very beginning to the end of Robinson Crusoe, readers are able to witness Crusoe’s religious “voyage”. This Journey is not only shown through Crusoe’s journal entries and inner thoughts but portrayed by the image of the sea throughout the novel. “I sincerely gave Thanks to God for opening my Eyes, by whatever afflicting Providences, to see the former Condition of my Life, and to mourn for my Wickedness, and repent” (142). The capricious sea represents Crusoe’s relationship with divine providence. “… as the Sea was returned to its Smoothness of Surface and settled Calmness by the Abatement of that Storm, so the Hurry of my Thoughts being over, my Fears and Apprehensions of being swallow’d up by the Sea being forgotten, and the Current of my former Desires return’d, I entirely forgot the Vows and Promises that I made in my Distress” (53). When the sea is violent and relentless Crusoe is instantly penitent and quick to ask God for assistance. However, when the sea is calm and quiet Crusoe seems to forget about God and just focuses on his possessions.

In some cases, it can be argued that the sea epitomizes not Crusoe’s relationship with God but God himself. Crusoe’s expeditions appear to be governed by the unpredictable conditions of the sea. When he gets shipwrecked multiple times, his life is left up to the fate of the waves that are able to either carry him safe to shore or leave him for dead among the rocks. Thus each time Crusoe heads out to sea illustrates not only his immense desire to abandon his middle-class title but his alacrity to surrender to the divine forces of providence that dictate his fate through the duration of his life.

Davis, Evan R, and Daniel Defoe. Robinson Crusoe. Broadview Press, 2010.