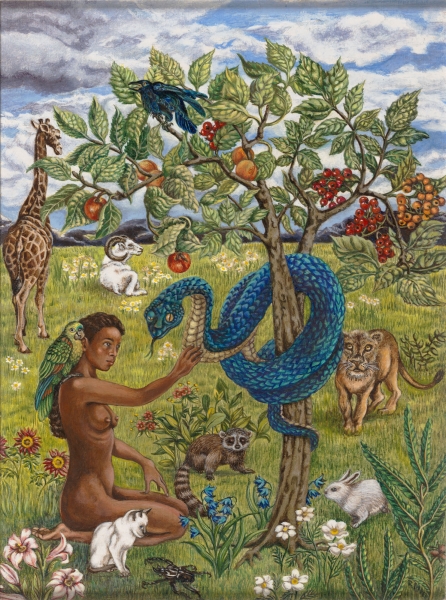

In Rose Piper’s Eve and the Serpent, she’s managed to construct an interesting adaptation and one that was entirely new to me. While the main theme presented in her painting was immediately and easily identifiable I feel that it’s noteworthy that she’s incorporated more elements than adaptation alone. She’s utilized intertextuality in the title of her painting to include Dem Bones (Gonna Rise Again), an old African-American Spiritual song; Dem Bones tells the story of Adam and Eve. By incorporating the song and the story of Adam and Eve she’s essentially created a visual bricolage, melding the original story and an adaptation of it together, creating her own adaptation in the process. Interestingly Piper chose to paint her adaptation minus Adam. With Adam being a central figure to the story I found it a curious decision, at first.

Then I stopped to consider who Rose Piper was. She was an African American woman that was born in 1917 and grew up in the Bronx, NY and drew upon influences from blues music in the 1940s and ’50s, during which time she painted some of her most notable works; Ackland has one such piece in circulation titled Slow Down, Freight Train. So it appears that Piper frequently drew upon music as the inspiration for her paintings. It might be assumed that as a woman and an African American woman growing up before & during segregation, and civil rights & women’s liberation movements, she felt marginalized.

Perhaps that’s part of the reason that she chose only to depict Eve and selected elements of Dem Bones to highlight some social issues that she had to deal with. In this way, her painting, Eve and the Serpent could almost be considered a parody as well. Piper seems to have masterfully taken multiple elements & sources and blended them together to create a truly unique adaptation to the story of Adam and Eve.

I think that the way in which Piper has chosen to incorporate the tree, snake and Eve into her painting and how she has portrayed the snake, in particular, is an interesting and refreshing adaptation on a story many know so well.